The United States’ top developer of green energy has spent nearly six years undermining a project vital to generating clean power in New England — a stance critics say belies the company’s branding as a leader in the fight against climate change.

Florida-based NextEra Energy has fought to block a transmission line for Canadian-generated hydropower by opposing it at two state supreme courts, the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission and the ballot box — twice. Its tactics, overseen in part by a public relations firm with a history of defending coal, recently led a Maine ethics agency to issue its largest-ever fineagainst an organization working on NextEra’s behalf.

NextEra’s campaign has delayed the power line’s construction for almost two years, leaving the region overwhelmingly dependent on natural gas. Its opposition highlights an uncomfortable reality for climate advocates: Powerful allies can turn into cutthroat adversaries when their profits are threatened.

“It just shows you that these companies are not fundamentally allied with the climate movement, not fundamentally on the side of climate progress,” said Leah Stokes, a professor at the University of California, Santa Barbara, who has studied utility opposition to climate policy. “They are just monopolies who sit on the bridge like a troll and try to protect their own profits.”

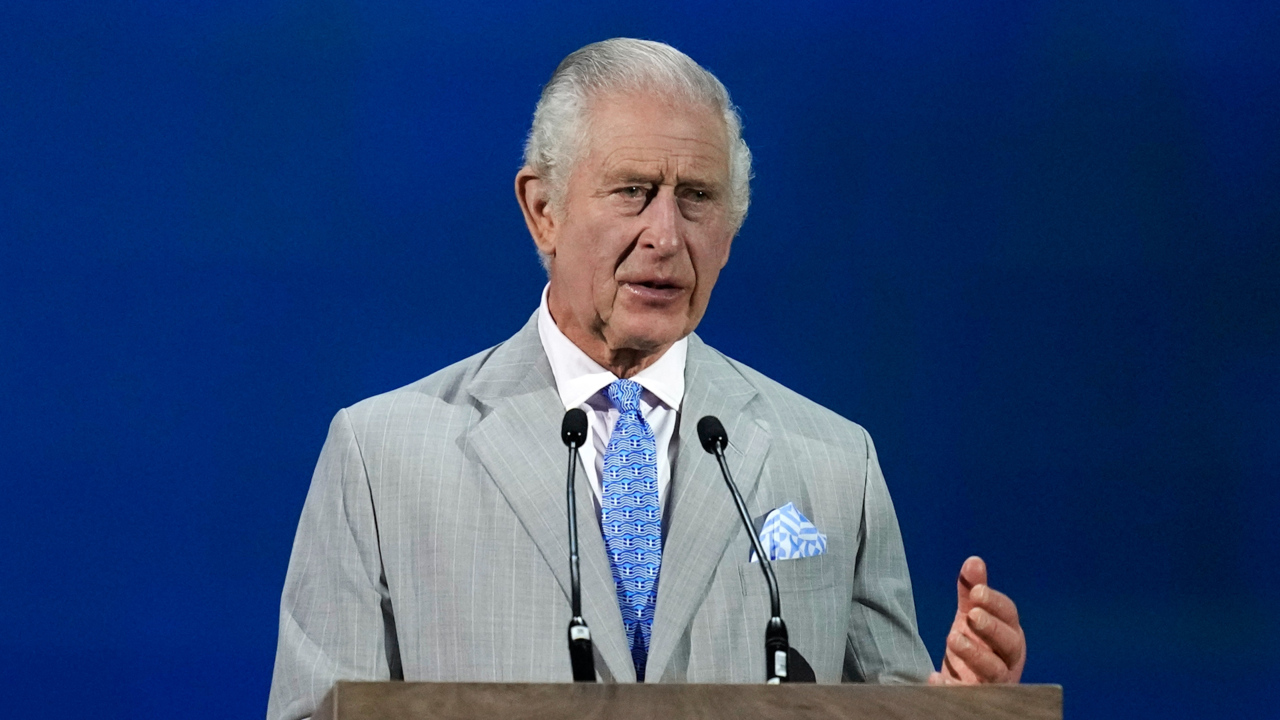

King Charles to COP28: World ‘dreadfully far off track’ on climate

lead image

lead image

NextEra spokesperson Chris McGrath defended its opposition to the line, saying no other company had done “more to drive the transition to clean energy” or “invested more in the nation’s electrical infrastructure in the past decade.”

But he argued that new transmission projects should be used for domestic energy, and the company has asserted in legal filings that the line might fail to deliver its promised environmental benefits. That echoes concerns expressed by some green groups about the power line’s potential impacts on forests and rivers.

“Our concerns around the transmission line in question stemmed from our belief that newly constructed transmission in the U.S. should support U.S. power generation — both new and existing clean energy,” McGrath said in a statement.

NextEra’s national fleet of wind and solar farms generates more renewable electricity than any other company in the country. It built the largest utility-scale solar project in New England, a 77-megawatt facility in Maine with enough power to supply about 15,000 homes. And its executives have been vocal about climate action, praising passage of President Joe Biden’s Inflation Reduction Act and calling for increased cooperation among companies and governments during climate talks last year in Dubai, United Arab Emirates.

But the company also has a history of defending its turf against other clean energy initiatives at a time of record-high global temperatures. NextEra’s campaign in New England echoes its fight against rooftop solar incentives in Florida, where it operates the country’s largest utility.

In New England, the power line, called New England Clean Energy Connect, represents potential competition for NextEra’s fleet of power plants.

Battles fought, battles lost

The transmission line would run 145 miles through Maine, from the Canadian border to a substation in the southern part of the state, where it would inject power generated by dams in Quebec into New England’s electric system.

The project has divided environmentalists, pitting those who say it’s needed to back up wind and solar against those who worry about the ecological impact of sawing down trees and damming rivers.

But nowhere has the fight been more intense than between power companies.

It began in 2018, when Massachusetts awarded a 20-year contract to the line’s two developers, Avangrid and Hydro-Québec. The contract would make the project one of the region’s largest power sources, providing enough electricity to meet about 7 percent of annual demand.

NextEra jumped into the fight almost immediately.

It operates Seabrook Station, a massive nuclear power plant in New Hampshire; an oil-fired power plant in Maine; and renewable facilities across the region. The company challenged the legality of the line’s power contracts in Massachusetts, contending they failed to meet state requirements for clean energy. The argument reached the state’s highest court, where NextEra lost.

In Maine, it challenged the project by arguing that utility regulators failed to consider its impact on renewable energy projects and state woodlands. It lost there, too.

And when New England’s grid operator determined that a circuit breaker at Seabrook needed to be upgraded to accommodate the injection of hydropower, NextEra asked federal regulators to ensure it was compensated for lost operating time. In response, FERC said Avangrid needed to pay for the upgrade, but not lost revenues. NextEra is appealing the decision in federal court.

Alison Silverstein, a grid consultant who served as an adviser to former FERC Chair Pat Wood III, said NextEra has a history of trying to shield its power plants from competition. In this case, those efforts conflict with Massachusetts’ climate goals, she said, because the state has directed its utilities to buy large amounts of hydropower to back up wind and solar energy.

“It would appear the public purpose and the will of the state is something that NextEra is willing to block,” Silverstein said.

‘Disturbing evidence’

In November, the Maine Commission on Governmental Ethics and Election Practices issued fines to two organizations connected to the company. Ethics committee documents and testimony show the groups were directed by consultants working on behalf of NextEra to block the line.

One of the groups, Alpine Initiatives, failed to register as a political action committee before making a $150,000 contribution to the Maine Democratic Party, a move that ethics officials said masked the source of payment from the public. The contribution was an attempt to ingratiate the consultants to Democratic officials as they looked for allies in their fight against the power line, the commission said. As part of a consent agreement, officials with Alpine Initiatives agreed to pay a $160,000 fine in exchange for not having to admit guilt.

The commission fined Stop the Corridor, a second group led by NextEra-hired consultants, $50,000 for failing to register as a ballot committee after it hired field workers to gather signatures needed to place a question on the 2020 ballot that asked voters to block the line. Stop the Corridor also signed a consent agreement that allowed it to avoid admitting guilt.

The Maine Supreme Judicial Court blocked the ballot question. But the following year, opponents of the line gathered enough signatures to add another question to the ballot that would have blocked the project.

NextEra spent more than $20 million to support this question, while Avangrid and Hydro-Québec, the Canadian utility that would send power to New England, put up more than $50 million in an attempt to defeat it. The question ultimately passed with the support of nearly two-thirds of voters, temporarily halting construction. Maine’s highest court later invalidated the result.

NextEra is not named in the two consent agreements, which refer only to “the client” who hired the consultants. But the paper trail leads back to the company. Stop the Corridor’s consent agreement notes that the client is identified in a campaign finance report attached to the deal. That report lists a solitary contribution: a payment of $95,726 from NextEra Energy Resources, the company’s renewable development and wholesale electricity arm.

During a November meeting of the Maine ethics commission, a lawyer “speaking on behalf of Stop the Corridor as well as the client” argued that the client would face “reputational harm” if the consent agreement identified it.

“The client is not being accused of any unlawful activity in this proceeding, and is facing no liability,” Paul McDonald, a lawyer at Bernstein, Shur, Sawyer and Nelson, told the commission. Bernstein Shur helped establish and run Stop the Corridor, commission records show.

But when questioned by Commissioner David Hastings III, a Republican, McDonald acknowledged the client was named in the campaign finance report attached to the Stop the Corridor deal. Hastings also asked if the client named in the Alpine Initiatives case was the same. McDonald said it was.

“I want to make very clear that the client is identified at least in exhibit B,” Hastings said, referring to the campaign finance report.

NextEra Energy did not respond to a question asking if it was the client. Instead, the company issued a statement echoing the terms of the consent agreement.

“NextEra Energy Resources is not a party to the consent agreements approved by the Maine Ethics Commission, and the agreements do not conclude that our company engaged in any wrongdoing,” said McGrath, the company spokesperson. “The agreements also do not conclude that our company failed to report any activity whatsoever.”

Avangrid took the opposite view. In a statement to POLITICO’s E&E News, the Connecticut-based utility said the ethics commission’s findings “provide direct and disturbing evidence that NextEra took nefarious and deceitful action to exclude competition and put its own bottom line ahead of the interests of New England residents and businesses.”

‘Subverting the whole plan’

NextEra is the most valuable publicly traded power company in the country, with a market capitalization around $117 billion, and has pledged to achieve “real zero” emissions by eliminating carbon dioxide pollution from its operations by 2045.

But analysts said NextEra’s fight against the transmission line resembles its opposition to rooftop solar in Florida. A joint investigation by the British newspaper The Guardian and the U.S.-based environmental news site Floodlight found that a lobbyist for Florida Power and Light, a NextEra subsidiary, had written large parts of a bill that would have gutted the state’s rooftop solar industry. Republican Gov. Ron DeSantis vetoed the bill.

J. Timmons Roberts, a professor of environmental studies at Brown University, said NextEra’s campaigns in New England and Florida are part of a wider trend in which utilities seek to protect themselves from competition.

“For them to be subverting the whole plan here is pretty devastating for the energy transition,” Roberts said. “We need, badly, all the wind and solar we can get on the grid, and we need the interconnection cable to Canada to balance the load for the times when there’s shortages down here.”

NextEra’s fight comes as state officials in New England seek to green the grid by awarding long-term power contracts to renewable energy developers, existing nuclear plants and hydropower operators.

That has prompted objections from power plant owners, who worry they could lose market share to competitors with fixed priced contracts. The transmission line received a 20-year power contract from Massachusetts to deliver 9.45 terawatt-hours of electricity annually, or enough to meet 7 percent of the region’s electric needs. The power will be consumed throughout New England because the region operates a single electricity system.

Canadian river power

It was against that backdrop that NextEra emerged as a chief opponent of the transmission line.

Roberts said NextEra’s legal challenges jeopardize climate efforts in New England, where five of the six states have legally binding requirements to make deep cuts in greenhouse gas pollution by the end of the decade. Those reductions are unlikely to materialize without a massive build-out of renewable energy, an increase in Canadian hydropower imports and the continued operation of Seabrook, he said.

Massachusetts officials estimated the line would reduce CO2 emissions by 36 million tons over its 20-year power contract. CO2 pollution from power plants in New England was 25.5 million tons in 2023, according to EPA data.

Stokes, of UC Santa Barbara, called hydropower “an amazing resource” that can reduce the region’s reliance on natural gas, which accounts for more than half of New England’s power generation.

“Would you rather have hydropower, clean hydropower from Quebec, or would you like to keep burning fossil gas?” Stokes said. “And my choice is I’m going to take the hydropower.”

NextEra questioned the environmental benefits of the transmission line. In its legal challenge over the line’s power contract in Massachusetts, it questioned whether the project would cut emissions to the degree promised, by arguing that the contract failed to guarantee additional imports of hydropower above what Hydro-Québec already sells to New England. The Massachusetts Department of Public Utilities and the state Supreme Judicial Court rejected that argument.

Persuading Democrats

The consent agreements released by the Maine ethics commission show how NextEra political consultants sought to influence public opinion around the power line.

NextEra, identified as the client in commission documents and testimony, hired the Hawthorn Group, a public affairs and consulting firm based in Alexandria, Virginia. The firm is perhaps best known for representing the American Coalition for Clean Coal Electricity during the congressional debate over cap and trade in 2009, when one of its contractors forged letters to lawmakers.

In Maine, Hawthorn turned to Bernstein Shur, a local law firm, to lead the campaign against the transmission line. Bernstein Shur and another Maine political consultancy, which was not named in the consent agreement, founded Stop the Corridor in April 2018 — around the time Massachusetts awarded the line’s developers a 20-year power contract.

Stop the Corridor arranged for opponents to attend municipal meetings, sought to shape public opinion through advertising, and worked with other groups to draft comments to state and federal agencies, the ethics commission said.

Bernstein Shur provided regular updates to the Hawthorn Group on phone calls held every two weeks. Sometimes, a NextEra employee joined the calls in listen-only mode. The client, later identified as NextEra, financed Stop the Corridor through the Hawthorn Group, the commission said.

As the 2018 midterm elections approached, Bernstein Shur contacted the Maine Democratic Party to provide a political contribution. The consultants thought Democrats would be more likely to oppose the line than Republicans, the consent agreement said, but they did not publicly disclose the reason for the contribution or the donor’s name.

The Hawthorn Group told Bernstein Shur not to reveal the client’s identity, so the consultants avoided taking any action that would require the disclosure of the company’s name, the ethics commission found. Instead, the law firm formed Alpine Initiatives to make the $150,000 contribution — Alpine’s only transaction during its 14-month existence.

Representatives from Bernstein Shur and the Hawthorn Group did not respond to requests for comment.

Annina Breen, a spokesperson for the Maine Democratic Party, declined to comment on Alpine’s contribution. “The MDP was never the subject of the commission’s investigation and no wrongdoing has been found or was ever even alleged on the part of the MDP,” she said.

NextEra also made alliances with environmental groups. Some of them shared the company’s view that the project would fail to cut carbon pollution and objected to its plans to saw down a 50-mile strip of forest for the transmission corridor in Maine.

The consent agreement names the Natural Resources Council of Maine and the Sierra Club as groups that worked alongside Stop the Corridor to oppose the project. The Sierra Club felt the region should be focused on building domestic renewables rather than supporting Canadian hydropower to meet its climate goals, said Matt Cannon, who leads the Sierra Club’s conservation and energy program in Maine.

“We did not feel like they had enough data to support the claim that it was clean energy,” Cannon said.

Asked if the Sierra Club had coordinated with NextEra, Cannon said, “Absolutely not.”

A spokesperson for the Natural Resources Council of Maine did not respond to requests for comment.

Avangrid resumed construction of the line last fall, but the project’s costs have ballooned from $950 million to $1.5 billion due to inflation. NextEra’s legal battle, meanwhile, continues in the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit, where the company is appealing FERC’s circuit breaker ruling. The next window for making the upgrade will come this fall, when Seabrook is scheduled to go offline to refuel.

The court battle appears to contrast with the message that a NextEra executive delivered during the COP28 climate talks in Dubai two months ago.

In an interview with the Atlantic Council, NextEra Energy Resources CEO Rebecca Kujawa hailed progress in cutting greenhouse gases from U.S. power plants. She added that much of the easy work had been done, and called on governments and companies to work together on deeper emission cuts.

“Our goals at COP is to help influence government policy, other commercial entities, stakeholders that have a part to play, to really engage with one another,” Kujawa said. “There is no single company, there is no single industry that is going to help us accomplish our goals.”

This story also appears in Energywire.