Consumers trying to avoid toxic chemicals in their nonstick cookware face convoluted advertising claims that can confuse even the most well-informed buyers.

Take Diana Zuckerman, who, as president of the National Center for Health Research, is more familiar than the average person with chemistry and toxicology. Still, she said, trying to determine which pans and cookware did not contain per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS), a class of toxic substances linked to cancer and other health problems, was no easy task.

“I, like many consumers, was fooled by all the promotional statements made about many types of cookware,” she said. “You shouldn’t need a doctorate to figure out what cookware is safe.”

But there’s limited oversight or enforcement of misleading marketing claims related to chemicals, with critics arguing the nation’s consumer protection system — which includes the Federal Trade Commission and the Better Business Bureau — is ill-equipped to handle them.

That’s despite test results conducted by an environmental watchdog showing cookware advertised as “free of” various kinds of PFAS often contained other types of the chemicals, thereby creating a difficult landscape for environmental- and health-minded buyers to navigate.

“The FTC is gun shy; I wouldn’t expect much of them,” said Rena Steinzor, a former attorney for the agency who now teaches food safety and regulatory law at the University of Maryland.

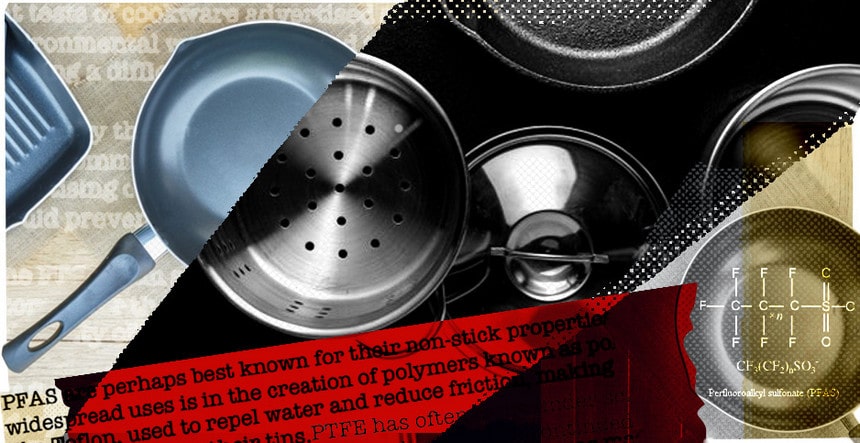

PFAS are perhaps best known for their nonstick properties; one of their most widespread uses is in the creation of polymers known as polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE), like Teflon, used to repel water and reduce friction, making it easier to flip fried eggs and release cakes from their tins.

PTFE has often come under scrutiny because it once was made using a PFAS called PFOA, which was discontinued in the United States years ago after being linked to cancer and other negative health effects. Now, American PTFE is produced using other types of PFAS, many of which have not been fully studied.

It is unlikely consumers would be exposed to dangerous levels of the chemicals from their cookware. But advocates argue PFAS do pose health dangers for manufacturing workers, as well as communities surrounding factories that have polluted groundwater. Because PFAS can remain in the environment for years, there are also questions about how to safely dispose of products containing the chemicals without contaminating additional areas.

As a result, environmentally minded consumers have increasingly sought cookware that doesn’t contain the chemicals. When they do, they are confronted by an alphabet soup of advertising claims, many of which can be misleading.

Late last year, the Ecology Center tested 24 nonstick products and found 79% of cooking pans and 20% of baking pans were coated with PTFE — despite many companies advertising those products as PFOA-free.

Items tested by the Ecology Center included products made by Cuisinart and Cooking Concepts, among other brands.

In the most extreme example, the Ecology Center found that the Ozeri stone Earth frying pan was made with PTFE despite it being marketed as “absolutely free of toxic substances such as APEO, GenX, PFBS, PFOS, PFOA” — some of the more researched and controversial PFAS.

In another instance, PTFE was found on a pan by Sunkitch Hotsun simply labeled “eco-friendly.”

“Companies often tell us certain chemicals are not in a product,” said Melissa Cooper Sargent, the Ecology Center’s environmental health advocate. “But when they don’t tell us what is in the product, we cannot easily make an informed choice.”

That is what happened with Zuckerman, who realized a few years ago that the cookware she already owned likely contained PFOA. She purchased a new set advertised as PFOA-free, and only later figured out — after hours of research — that it likely contained PTFE instead.

“No one should have to go through that,” she said.

FTC’s ‘Green Guides’ and deceptive advertising claims

On paper, FTC would agree.

The agency’s “Green Guides,” last updated in 2012, help interpret federal law prohibiting misleading and deceptive advertising claims for situations involving chemicals, or claims about products’ environmental impact.

The document specifically warns companies not to describe products as “free of” one chemical if they contain other, similar chemicals “that pose the same or similar environmental risks as the substance that is not present.”

“Sometimes what companies think their green claims mean, and what the consumers really understand are two different things,” the agency’s website explains. “FTC’s Green Guides are designed to help marketers avoid making environmental claims that mislead consumers.”

Other FTC documents describing the agency’s general enforcement approach to pursuing cases state that the agency is more likely to investigate deceptive claims if “the act or practice is likely to affect the consumer’s conduct or decision with regard to a product or service.”

But the agency has pursued just one case involving chemical claims in recent years.

FTC entered into a consent decree with four paint companies — including Benjamin Moore & Co. — for claims that their paints would not emit volatile organic compounds directly after being applied.

Promotions of the products explicitly claimed the paints were safe to use around pregnant people and babies, despite the companies not having any evidence to support that. The companies settled with FTC in 2017, agreeing not to make such claims unless they could prove only “trace” amounts of the chemicals were being emitted.

Steinzor said the agency should be chasing down misleading claims about additional chemicals.

In 2013, when she was working for the Center for Progressive Reform, she petitioned the agency asking it to investigate plastic food container manufacturers that advertised their products as “BPA-free” when they still contained other chemicals that also disrupted the endocrine system.

“Such claims are deceptive because they mislead reasonable consumers into believing that the products are free of all chemicals that pose the same or similar health and environmental hazards as bisphenol A,” she wrote at the time.

The agency never responded to the request.

“The FTC is the premier agency for policing consumer protection, and false chemical claims should be a big concern to them,” she said recently. “They should figure out how to do it; otherwise, the Green Guides are not worth the paper they are written on.”

The FTC’s Office of Public Affairs declined to comment on the criticism.

In a statement, the office said only, “When and if the FTC decides to open an investigation depends on a range of factors including consumer complaints, the amount of harm allegedly caused by the conduct, staff, resources and comments received from industry, among other things.”

Competitors as judges?

Another little-known option available to consumers is filing a complaint with the BBB National Programs’ National Advertising Division, which was founded in 1971 in response to consumer calls for more truth in advertising. NAD investigates claims of misleading advertising and asks marketers to “substantiate” what they are telling consumers. If advertisers can’t back up their claims, NAD puts a stop to them.

Often, complaints are filed by competitors, which NAD Vice President Laura Brett said is actually helpful for flagging misleading advertising claims.

“Competitors are often very good judges about whether or not claims they are competing against are supportable,” she said.

Complaints, along with supporting evidence provided by the marketer, are reviewed by an NAD panel of advertising experts. The organization does not employ any technical scientific experts to help evaluate claims about chemicals. Rather, Brett said, the panel operates “much like a court would” in evaluating the evidence.

That was the case in 2015, when NAD found a shampoo company was misleading consumers with claims that its products contained “zero SLS or SELS,” which consumers sometimes avoid if they are worried about skin irritation from soaps, because the shampoos contained another irritating chemical.

But NAD’s process may not be well-equipped to handle instances where evidence about chemicals’ harms is still emerging, as was the case in 2012, when it evaluated claims related to PFAS and nonstick cookware.

Back then, the organization agreed to investigate claims made by GreenPan that its cookware was “PFOA-free” and “PTFE-free” in a complaint brought by DuPont — the chemical company that previously manufactured Teflon using PFOA.

DuPont alleged GreenPan’s claims unfairly disparaged PTFE coatings by implying they were all unsafe and all manufactured with PFOA.

Though GreenPan maintained it was not insinuating that its products were safer than PTFE-coated pans, NAD sided with DuPont, determining that as PFOA production had been discontinued, there was no evidence that PTFE coatings were more harmful to the environment than Greenpan’s nonstick coating.

NAD ultimately recommended GreenPan stop claiming its product was free of PFOA — even though the products are free of all PFAS.

In the years since, research into some PFAS used to replace PFOA in PTFE has linked the compounds to similar health and environmental effects.

Brett would not discuss the specifics of that case but added, “I understand that the science has changed since then.”

“If we looked at the issues again, our analysis would reflect whatever the current science is,” she said. “I don’t know a lot about nonstick chemicals and what is deemed safe today or not, but if we were going to look at this product category again, we would want to understand the broad concerns that the science community has voiced about a particular chemical that is used and whether they are more concerned about some chemicals than others.”

Steinzor said the case shows that “the private market can’t take care of the mess” and that FTC should be doing more.

GreenPan did not respond to requests for comment.

DuPont spun off its PFAS manufacturing in 2015 and redirected comment to the company Chemours Co. A spokesperson for Chemours said the company does not typically comment on such issues.

Protecting vulnerable consumers

Navigating company claims around chemicals like PFAS can be especially challenging for communities that already face disproportionate environmental impacts.

Sylvia Orduño, an organizer with the Michigan Welfare Rights Organization, said nonstick cookware is an important example of how environmental justice issues can intersect with consumer protection issues. Speaking at a panel hosted by the Environmental Law Institute, Orduño said nonstick cookware is “one example of how these sorts of problems are in our homes, are in our communities.”

Orduño wants to see more education in communities of color and low-income communities so that residents understand the connections between the products they purchase and contamination.

“We’ve also got to be better about how we communicate what we need through consumer protections and through education so that our communities understand that you really don’t want to be cooking with that,” she said.

Concern about the chemicals is already spawning companies with environmentally friendly branding. Those include Caraway Home Inc., which uses natural ceramic in its pans rather than PTFE coating and shared its test results with E&E News indicating the products do not include major PFAS compounds.

Sargent of the Ecology Center said ceramic is a preferred alternative to PTFE coating, and the organization’s testing found that items marketed as “PTFE-free” appeared to be free of PFAS. Other chemicals could still be present in those products, but multiple experts recommended ceramic alongside stainless steel and cast iron as alternatives for consumers seeking pans with some properties similar to those that use PFAS.

For Zuckerman, cookware is just one example of how federal regulators have failed consumers when it comes to secret chemicals in products. Though she hopes the Biden administration will step up oversight efforts, she is pessimistic about the scope of the problem.

“It’s impossible to know everything,” she said, calling it a case of “buyer beware.”

She added, “Consumers cannot trust anything they see unless they educate themselves first and really stick with the simplest information and follow it.”